Southend United and York City played out a 1-1 draw on the opening day of the 2024/25 National League season at Roots Hall on Saturday afternoon.

In this article, I’ll break down the tactical battle between Kevin Maher and Adam Hinshelwood; assess both side’s pressing structures; and explain why York had so much of the possession.

Southend’s build-up

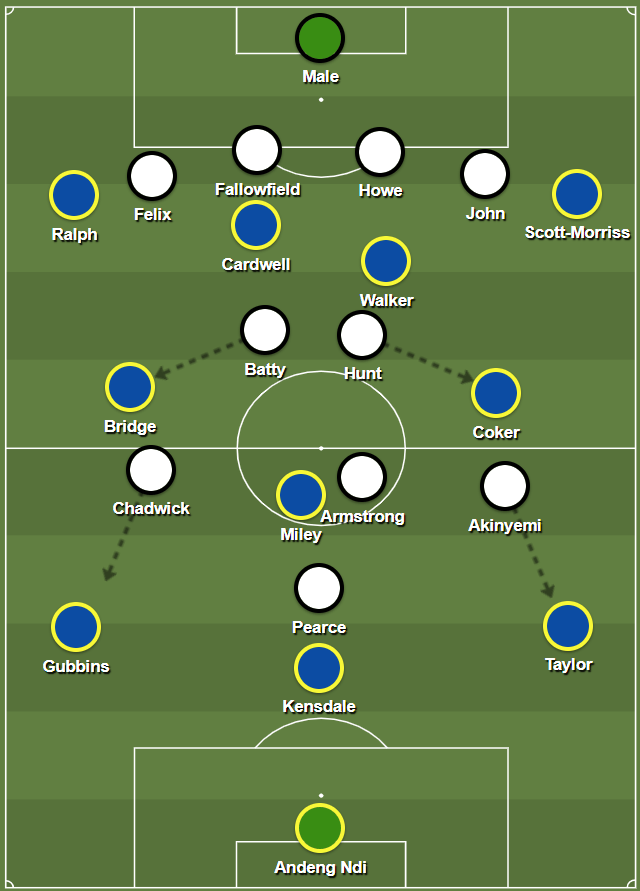

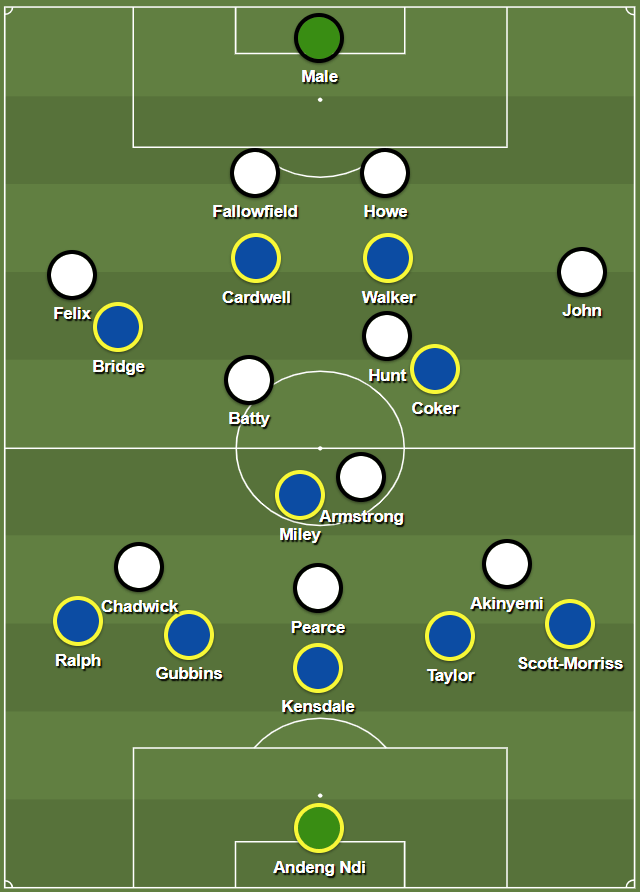

Southend aimed to build play in their usual 3-diamond-3 shape. To counter, York pressed in a zonal 4-2-3-1 shape; by asking their second-striker, Marvin Armstrong or Ricky Aguiar, to drop deeper and man-mark Southend’s #6, Cav Miley.

As we can see from the above tactics board image, this meant that York had players in close proximity to Southend’s all across the pitch, and could shift from a zonal press to a man-to-man one with ease.

Consequently, Southend were forced to ‘go long’ much more than they would have liked, rather than reliably play through the press, and struggled to control possession and progress forwards safely. After playing long, they had to challenge for duels in order to initiate attacks, look to win second-balls, and use set-pieces to their advantage. Southend’s goal – a Gus Scott-Morriss header – was via a set-piece.

Southend lacked the movement and rotations in order to play through York’s press with reliability, which were required because they didn’t have a numerical advantage in the build-up.

Previously, we have seen James Morton drop back to act as the situational left-sided centre-back after Nathan Ralph had pushed forwards, with Jack Bridge inverting into the midfield. However, with Ralph being used at left wing-back, Joe Gubbins playing on the left of the back-three, Bridge being used centrally, and Morton not included from the start, this rotation was not possible.

Alternatively, we have also seen Harry Taylor invert from his right-sided centre-back area into the midfield, in the past. If he attempted this on Saturday, it may have moved York’s left-winger inside the pitch, opening up the passing lane into Southend’s right wing-back, Scott-Morriss.

However, perhaps neither of these methods would have worked against York, as they pressed zonally rather than man-to-man.

York’s build-up

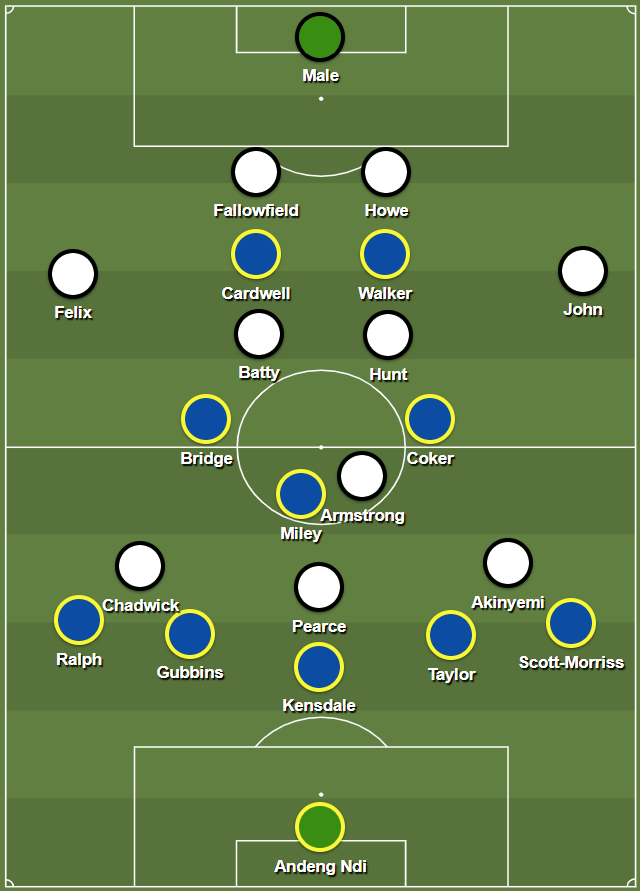

York built play in a 4-2-1-3 shape, with their second-striker, Armstrong or Aguiar, occupying the space between the lines. Southend looked to press from their compact 5-3-2 shape (below), and they did a pretty good job at forcing York to ‘go long’ from their goal-kicks, when they pushed their wing-backs slightly higher to put pressure on York’s full-backs. However, from open play, they weren’t able to implement this press successfully with great regularity for a number of reasons, as I will now explain.

As we can see above, Southend’s striker’s, Harry Cardwell and Josh Walker, were tasked with both pressing York’s centre-backs and shadow-marking their double-pivot. If they pressed, this was backed up by Southend’s #8’s, Oli Coker and Bridge.

The issues centred around York having a numerical advantage in the build-up. They had six players in the first two lines (4-2 build), and Southend often only committed four players to the high press from open play.

When a York centre-back had the ball, a Southend striker would press them. This made it difficult for the strikers to then press York’s full-back as well. However, if the striker did manage to press the full-back, this didn’t trigger the man-to-man press.

It would have been more effective if Southend’s far-side striker came inside the pitch to mark the ball-side centre-back. This is because the two spare York players would have been on the opposite side of the pitch, and York would have struggled to find them consistently. A zonal turned man-to-man press, as illustrated below.

Southend had a 5v3 numerical advantage in the last line, and would have fancied their chances of winning the loose-ball duels that would have occurred, had York have been forced to ‘go long’ in this instance.

But because this didn’t seem to trigger the man-to-man press, York’s full-back could pass back to his centre-back, they could retain possession, and reset.

If, more likely, Southend’s ball-side #8 pressed the full-back instead, there were still issues present. As both Southend’s far-side #8 and Miley were both occupying opponents, they couldn’t always change marking responsibility and press the now free York midfielder. This often left York’s ball-side #6 in space – if the Southend #8 didn’t effectively block the passing lane into him (below).

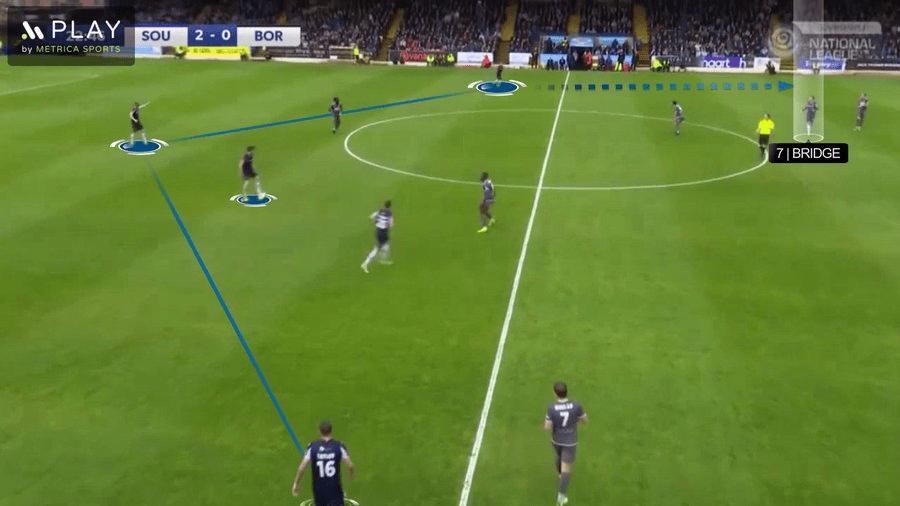

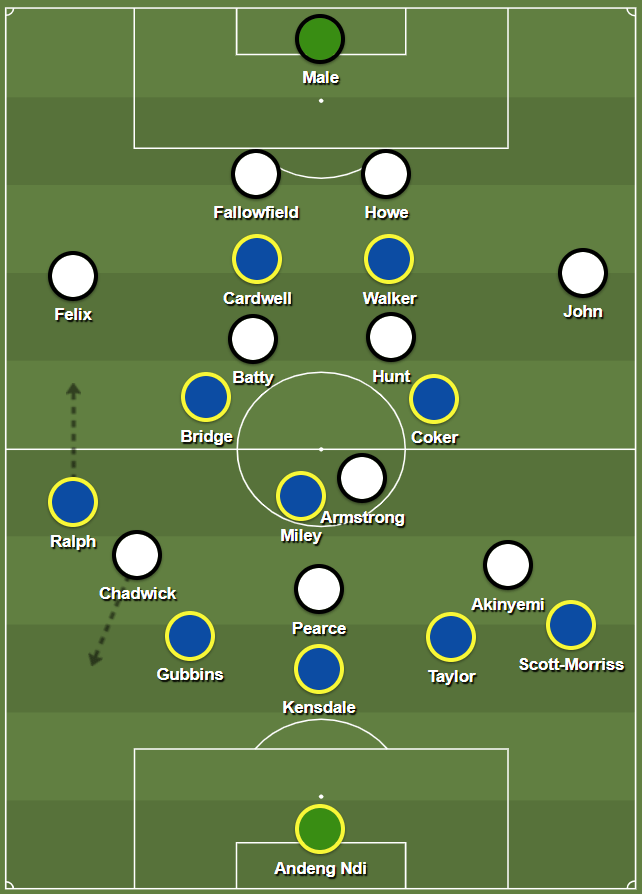

And finally, a Southend wing-back, usually Ralph, would sometimes begin to step out from the last line to press York’s full-back. However, because the distance he had to cover to do so was so great, it often gave York’s right-back time to play a pass over him. Once met by York’s right-winger, Billy Chadwick, he could isolate Gubbins out wide, as we can see below. This was York’s main source of creativity in the first half.

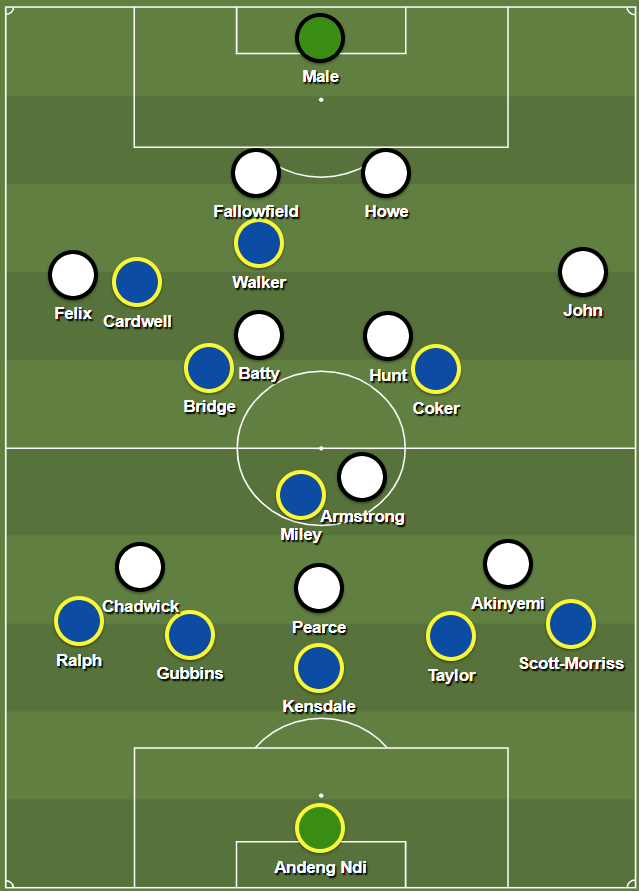

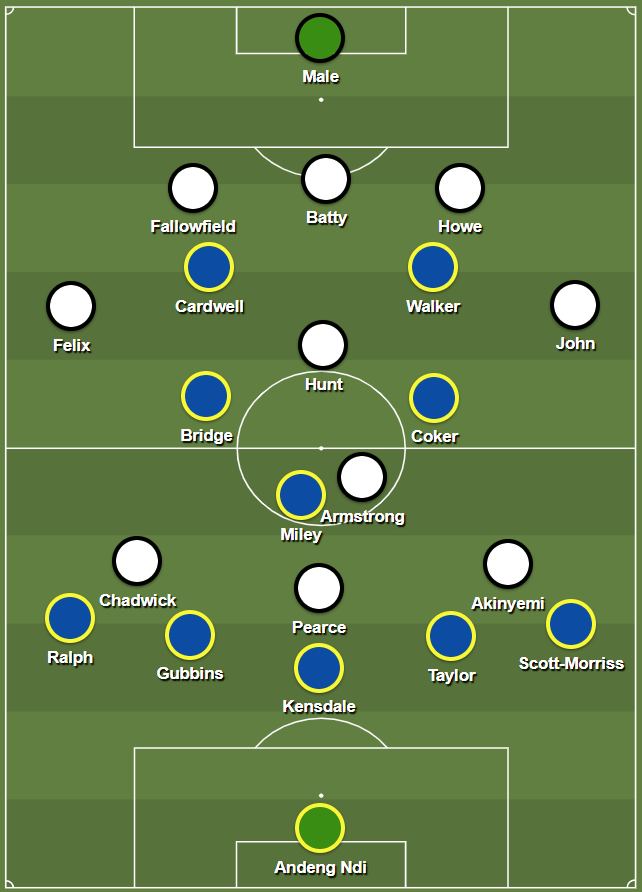

As the match went on, York began to stagger their double-pivot at different ‘heights’. They dropped one of their #6’s, usually Dan Batty, deeper, between their centre-backs, creating a 3-3-1-3 shape (below).

As Southend were marking zonally in midfield, in order to maintain compactness, their #8’s were reluctant to follow Batty when he dropped deeper. Additionally, with Southend’s strikers already responsible for pressing York’s centre-backs, it gave them a 3v2 numerical advantage in the first line of their build-up. This is significant, because it allowed Batty to find a lot of time on the ball in order for him to play long passes forwards to pick out forward players or runs from deep.

Southend continued to press with just two players in the first line until striker Danny Waldron was introduced to the action.

This slight change of shape also allowed York to get their full-backs higher up the pitch quicker, enabling them to join the attack and be part of some fluid positional rotations in the final-third, rather than having a large distance to travel after being involved in the first line of build-up, previously.

In addition, the shape also meant that York’s right-sided centre-back, Ryan Fallowfield, could push forwards. Fallowfield is primarily a right-back, meaning that when he was asked to move forwards up the right-side of the pitch to help the attack, he was comfortable doing so. In these instances, York’s other centre-back, Callum Howe, wasn’t isolated, because Batty was now acting as a situational centre-back, after dropping deeper.

As Fallowfield was, on paper, a centre-back who was being marked by a Southend striker, he often went unmarked in the final-third, giving York an additional player in attack.

Conclusion

To summarise, York pressed Southend’s build-up with a zonal turned man-to-man press all across the pitch. This meant that Southend struggled to reliably play through the press, were forced to ‘go long’, had to win loose-ball duels in order to initiate attacks, and were a threat from set-pieces.

York had a numerical advantage in their build-up phase, and Southend’s press wasn’t implemented with great success, for the reasons explained earlier.

As Southend started the match with five defenders on the pitch, there wasn’t much flexibility to change their pressing structure once it was clear that it wasn’t working. Bridge is usually the left wing-back, and, because he’s a natural left-winger, it allows Southend to switch from a back-five to a back-four with ease – especially when Ralph is used as the left-sided centre-back. This allows Southend to put more pressure on the ball high up the pitch. However, as he was used in midfield, there was less flexibility to switch pressing structures.

Although York had a lot of the ball in non-threatening areas of the pitch to begin with, with the amount of possession that they had, it was no surprise that they eventually found a way to break Southend’s defensive resilience after going behind. They had the momentum, and, together with Southend not being able to reliably play through the press and sustain attacks for themselves, they managed to control the majority of the possession, and it was no surprise that they found the equaliser.

Once York had progressed up the pitch, Southend did look threatening in transition. Cardwell and Walker are excellent players in offensive transition as they both have the necessary athleticism to get Southend up the pitch, and cause issues in open spaces.

You must be logged in to post a comment.