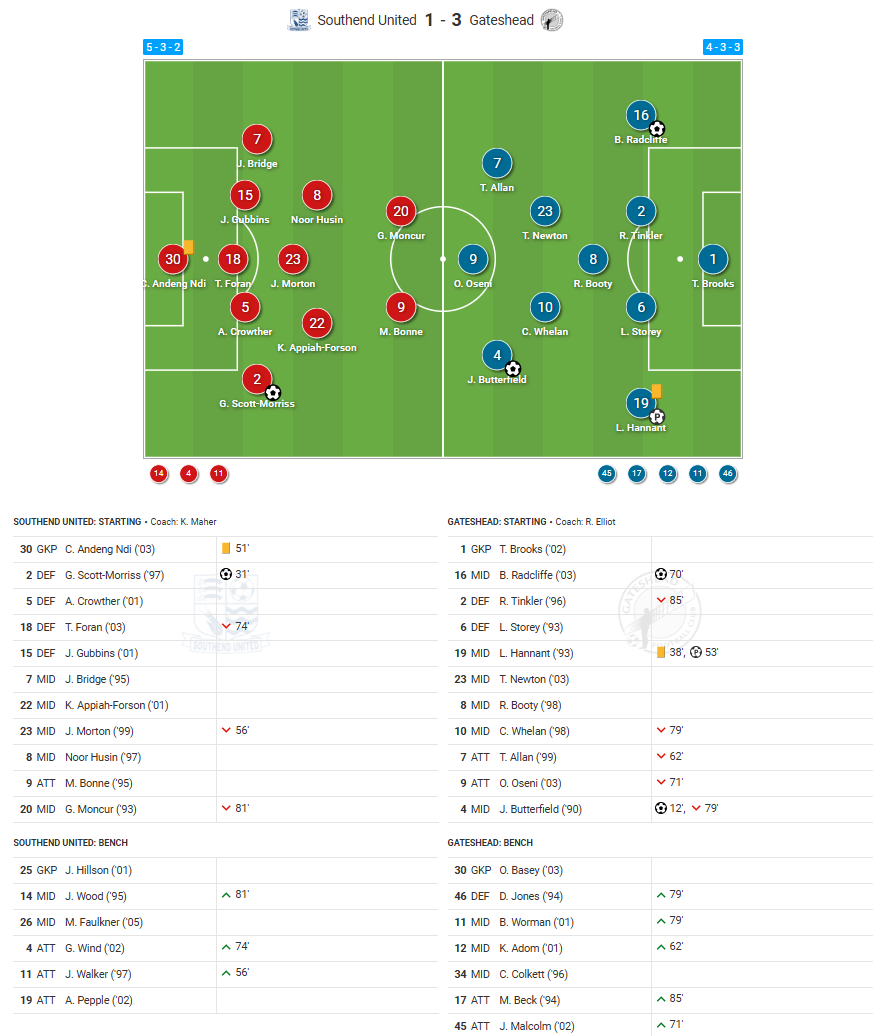

On Saturday, Rob Elliot took charge of his final match as Gateshead manager when his side visited Roots Hall to face Kevin Maher’s Southend United.

In this article, I break down the tactical battle and explain how Gateshead picked up the three points in a 3-1 victory.

Gateshead’s attack

Gateshead lined up in a 4-3-3 formation, but there was some flexibility to this shape depending on the phase of play. During their build-up, for instance, they would push their left-back, Luke Hannant, high and wide to hold the width; and Jacob Butterfield would tuck inside the pitch. This would create more of a 3-diamond-3 shape, with Butterfield acting as the #10 behind their centre-forward, Owen Oseni.

Gateshead mixed between playing short or long passes from their goal-kicks; either by using their goalkeeper, Tiernan Brooks, to launch the goal-kick, or their central centre-back, Robbie Tinkler, to play short towards him.

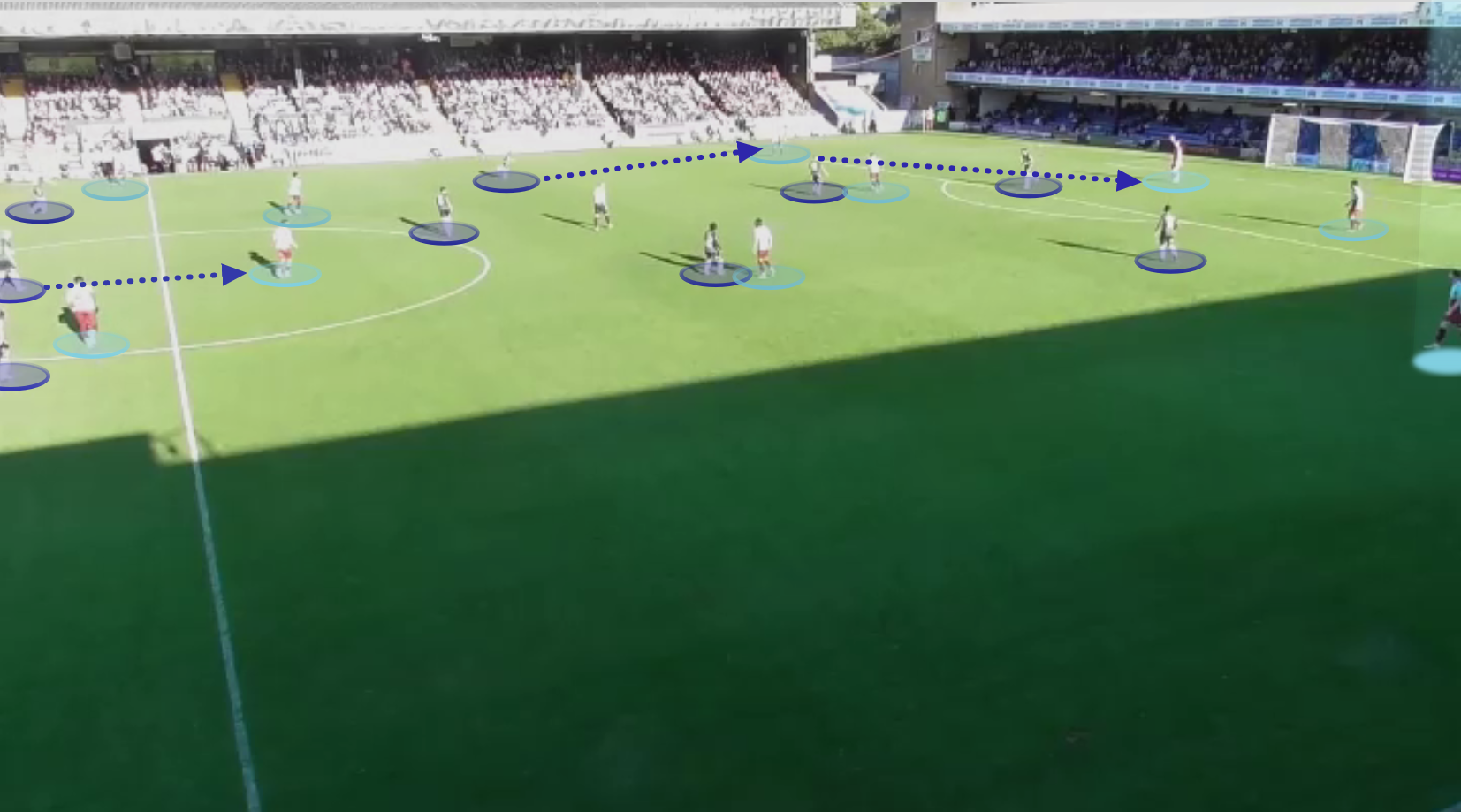

When Gateshead did ‘play out’ from their goal-kicks, Southend were brave and pressed in man-to-man fashion all across the pitch.

Southend’s centre-forward, Macauley Bonne, led the press by shadow-marking Gateshead’s right-sided centre-back, Ben Radcliffe, and pressing Brooks whilst blocking the passing lane into Radcliffe. This released Southend’s left wing-back, Jack Bridge, to be aggressive and press Radcliffe if Gateshead found him, and the press was backed up by the left-sided centre-back, Joe Gubbins. Every other Gateshead player, except one, was man-marked and a Southend defender could even step into the midfield to press Butterfield if needed. The only spare Gateshead player was their far-side centre-back, Louis Storey, who couldn’t safely be reached by a teammate (below).

This man-to-man press that Maher went with was brave considering the top technical quality that Gateshead possess all across the pitch, but it was effective as it stopped them from building play safely and sustaining attacks straight off the back of their goal-kicks.

However from open-play, Southend’s press was slightly less aggressive – but understandably so. They pressed in a 5-2-3 shape, with Keenan Appiah-Forson and George Moncur either side of Bonne, who both shadow-marked Gateshead’s #6, Regan Booty, and pressed Tinkler. This left Gateshead with a 3v3 in the first line of their build-up, but they could rely on their goalkeeper Brooks’ ball-playing ability to create a +1 in this moment (below).

When Bonne left Booty to press Tinkler, it was the responsibility of either Noor Husin or James Morton to jump to press him from their deeper midfield position. The issue with this was that, because of Gateshead’s excellent technical quality, it only took a split second for them to bounce a pass off Booty to find Tinkler once Boone left him to press Brooks. There was a 3v2 numerical advantage for Gateshead, and this was enough for them to reliably find the spare man in the build-up.

Gateshead’s midfielder Callum Whelan was particularly difficult to press, due to his ‘high-to-low’ positioning. He regularly started in the last line for Gateshead but could drop into the midfield to receive passes there, instead. This meant that Gateshead’s shape was fluid depending on Whelan’s positioning. It could either be interpreted as a 3-2-5 if Whelan was pushed high, or a 3-diamond-3 if he was in the midfield alongside Booty and Tyrelle Newton.

This caused issues for Southend, as who was supposed to press Whelan? Appiah-Forson was told to be aggressive and press the centre-back, but Gus Scott-Morriss couldn’t always step into the midfield to press him. Whelan’s high positioning also contributed to Gateshead’s opening goal, which I will explain in a moment.

Overall though, Southend’s pressing structure worked fairly well. Of course, Southend’s press was never going to be able to work 100% of the time. Gateshead are too good in-possession for that to happen. When Gateshead could build play safely and managed to sustain attacks in the final-third, Southend’s 5-4-1 defensive block did a good job at protecting goalkeeper Collin Andeng Ndi in these moments, and Gateshead didn’t create too many dangerous moments from settled attacks.

When play broke down, because Gateshead have such an appetite to (counter-)press, they could win the ball back quickly and sustain pressure on the edge of Southend’s penalty area. When Southend did win the ball back and could look to counter-attack, Bonne was either too isolated to reliably hold the ball up, or not athletic enough to cause issues in transition by himself. This again allowed Gateshead to sustain attacks in the first half.

Gateshead aren’t just a difficult side to play against because of their ability to consistently play through pressure, though. They also have dynamic players who can make penetrative runs in-behind opposing defences which helps them to bypass the press; either by playing over and beyond the block, or by running into the channels.

This makes Gateshead such a difficult side to come up against. If you’re brave and press aggressively, they can hurt you with runs in-behind; but if you’re passive and keep a compact defensive block, it makes it easier for them to progress play, ask questions, counter-press and sustain pressure.

On balance, Southend’s approach was probably the right one. After 90 minutes, both sides had accumulated a 1.05 expected goals (xG) figure, and possession was split fairly evenly. However, all three of Gateshead’s goals originated from balls played in-behind Southend’s defensive line. So let’s break them down…

As earlier mentioned, Gateshead’s left-back, Hannant, was positioned high and wide during their build-up phase. However if he decided to drop to offer a passing option, it was the responsibility of Southend’s right wing-back, Scott-Morriss, to jump to press him.

This is how Gateshead scored their first goal, as illustrated below. Hannant dropped deeper, Scott-Morriss was slightly too slow to apply pressure – which was fine – except that Hannant played a first-time pass over Southend’s high defensive line. This left Gateshead in an advantageous 3v3 situation (because of Whelan’s high positioning) and they managed to exploit the space in-behind to score.

Gateshead’s second goal came from one simple long ball after played had broken down from a Southend attack. Although their rest-defence still left them with a 2v1 numerical advantage in this moment, Southend’s defenders got their positioning wrong and allowed Oseni to be in the middle of the two of them. He ran in-behind and Andeng Ndi fouled him to give away a penalty.

Gateshead’s third goal was via a corner, however the build-up to the goal also came from a run in-behind. Southend had just turned possession over themselves and were attacking in transition at speed. However once play had broken down, because they attacked at such speed, they weren’t in an optimal position to counter-press.

The pivot hadn’t been able to catch up to the attack, and there was a lot of space between the lines. Even if the pivot had then been aggressive in this moment, it would have left a huge space in-between themselves and the defence which could have been exploited.

This lack of compactness allowed Gateshead time on the ball to move out of their penalty area, and another long pass could be hit into the channel. Southend just about defended it, albeit conceding a corner, but Gateshead scored from the resulting set-piece.

Southend’s attack

But what about when Southend had possession? From the start of the match they launched their goal-kicks and from open-play, because of Gateshead’s appetite to press with intensity and force turnovers, the aim was for Southend to play over Gateshead’s press. Southend would regularly aim these passes towards Bonne for him to challenge for aerial duels, and then they’d look to counter-press high in order to initiate attacks in Gateshead’s half.

This is how Southend’s goal originated. A long pass was played to Bonne, Moncur was first to the loose-ball, and he played a first-time pass over Gateshead’s defence for Appiah-Forson to run onto (below). He got Southend up the pitch, and set the ball back for Scott-Morriss to score.

These penetrative runs in-behind are what makes Appiah-Forson unique to Southend’s midfield, and it’s an attribute that Southend have lacked since Wes Fonguck’s departure in the summer.

The issue with this method of ball progression is that it wasn’t sustainable. The reliance on Bonne to challenge for aerial duels and the midfield to successfully counter-press with consistency in order to get up the pitch is a risky one. Especially so when we consider that the combination of forward options Southend had on the pitch aren’t tremendously physical. This meant that possession was too easily turned over, which played into Gateshead’s hands. However, Southend still created some fairly good chances off the back of this method.

When Southend managed to sustain attacks in the final-third, it was a very noticeable tactic of Gateshead’s to make sure Bridge, Southend’s most creative player, was doubled-up on at all times. This required excellent concentration from Gateshead to maintain this throughout the full 90 minutes.

However, Bridge was too often left isolated and lacked the support and movement required to have much of an impact on the match. Gubbins was selected as the left-sided centre-back in Nathan Ralph’s absence, and he lacks the athleticism required to reliably make overlapping runs beyond Bridge to take defenders away from him.

Once Gateshead had re-taken the lead in the second half, they were more inclined to sit in a compact mid-block rather than press aggressively from the front. This allowed Southend more time on the ball, and they could build attacks safely with greater regularity. After going behind in the second half, Southend had a 61% possession share and managed to sustain attacks much more frequently. There were more opportunities to put the ball into the penalty area, but although they create some decent chances they couldn’t reduce the deficit. Southend only accumulated a 1.05 expected goals (xG) figure overall, although this did match Gateshead’s.

Conclusion

To conclude, Southend did a very good job at preventing Gateshead from building attacks off the back of their goal-kicks, and were brave in the pressing moment.

Although the structure was pretty good, Southend probably lack the defenders available at this moment in time to be absolutely top at defending in a high defensive line; with Harry Taylor and Nathan Ralph unavailable, and Ollie Kensdale leaving the club. The fact that it was an entirely new back-three combination has to be taken into consideration as well.

A combination of this and Gateshead’s tactical flexibility, where they can both play through pressure and make runs in-behind, won them the match.

You must be logged in to post a comment.